Biblio-fille

Readings from a book lover, teacher, teacher-librarian.

Des lectures d'un bibliophile, enseignante, enseignante-bibliothécaire.

Currently reading

Another great Genevieve Lenard read

A few more editing errors than the other titles but a great continuation of the series. Though I missed Nicki's sass, I loved Bree and hope she becomes a regular or even gets a spinoff.

In terms of story, I liked the narrative and characters. I liked both Aisling and Eric, though I think their characterisation skewed older than stated. Eric's reaction to his mom struck me as authentic though. Lots of kids at that age will make a decision and, from a mistaken attempt to seem 'grown up' will refuse (or not understand how) to admit a mistake.

It was obvious to me that Cor was going to be bad given his name (Cor->Corvid/Corbeau->Raven->trickster) and the circumstances of his appearance, and understandable that Eric, being only 12 wouldn't really question his motives. It was much less believable, however, that no one, even the adults really questioned Jake's presence or motives, especially given the history of relations between city/rez and the apparent danger for the family's secrets. I wouldn't have thought them so welcome to a stranger in such circumstances. Eric, yes, because he's vulnerable, but as soon as Aisling is surrounded by her family, she's no longer a good victim. I kept waiting for him to have some important narrative role. There really wasn't any foreshadowing of his evil and I'm not decided if that was because of the naivete of the narrative voice, or a weakness of the writing.

Most of the mythological elements worked with what I already knew of First Nations mythology with the exception of Raven as a destroyer. Trickster, certainly, and creator of the earth in some versions, but I've never come across him as an apocalyptic character. To me that sounds closer to the Eurocentric symbolism of ravens as harbingers of death, so I wonder how much of that portion of the story was 'fanatsy' and how much was based on the mythologies Paquette knows from his elders.

I have to point out some deficiencies with the actual book layout/design. When I was breaking in the spine, I noticed there was something off about the pages, but had to really look to figure out what it was. The paragraphing isn't standard and the extra spacing between dialogue and narrative was really distracting. I eventually got over it as I just started reading faster, but I have to say it's a big strike against the book being used in classrooms where we struggle to teach students how standard paragraphing works. If the formatting were consistent, I could use it and discuss it with students as a comparative to standard style, but it doesn't even seen to follow its own conventions and I can't see it being a stylistic choice that mirrors any aspect of the narrative either like the oral style of Wagamese's Keeper N' Me, for instance.

1

1

I really enjoyed this book. I especially like the cover. I was tempted to buy the hardcover just because the dust jacket looked so good, but my thriftier self won out. The text of the title drew me at first. It game me a good sense of era, and now that I look at it again, the details are impressinve: the spike (though that's not what a railway spike looks like) and the key, the funeral car at the top, the length of the train represented by the fact it curves from the foreground to the background, and the white figures of Maren and WIll leaping atop the cars.

In terms of the story, I really enjoyed it. Oppel has a great sense of scene. I was initially intrigued because of the golden spike narrative. I live near the original terminus of the CPR, and a local community holds Golden Spike Days every July. So it drew me in, then disappointed when we didn't get further west than Craigellachie. But all the historical characters were interesting, and Will's outsider's view of the execs was refreshing and would certainly be easier for kids to understand.

While the time jump was unexpected, the description of the train was awesome. I didn't have any problems with suspending disbelief as I read this sort of thing often. I enjoyed Will's character and his self-doubt...mostly internalized doubt from the others in his life, which I think is really true for many kids, especially when they're talents and interests lie outside the capitalist status quo. That's something many of my own students struggle with a lot. I also really enjoyed Maren's character, especially the degree to which she controlled her own life. The allusions to Dorian Gray were fun, and if you know the story, foreshadow Mr. Dorian's demise pretty clearly.

The marginalised characters like Dorian (Metis), the Chinese workers, the colonists, and the "Natives", however, don't sit entirely well with me. I like the fact they're included and that Will recognizes the class differenences and the injustices therein, but the fact that the story ends with Will running away to the circus without ever discussing the injustices with his father as he had so wanted to do was disappointing. There's enough information about these groups to recognize their marginalisation, but there's no resolution or real building of the issue. Not that I expect the injustice to be resolved, that wouldn't be consistent with the pot's internal authenticity, but it does mean that students in class will need more direct guidance with those elements than perhaps otherwise. Of course, that's a problem with anything steampunk anyway, as not all students can be expected to tell what's real history from Oppel's revisioning.

In terms of the writing, I enjoyed the dialogue and some of the observations. Maren's description of how playing a character can help you get over stage fright (p. 182) is especially strong for me. I always tell my students that really throwing yourself into a character makes acting for an audience much easier even if they don't always believe me or do it. Of course, their safety isn't at risk like Will's is, so he has more motivation to delve into character than they do.

While some may not enjoy the conclusion of the book, I think it's important that we DO see Will finally assert himself at the end of the story. Throughout the entire story he's been struggling to really find himself, and to assert his own beliefs (over his father's for instance). It's clear even to his father by the end of the book that Will does have what it takes to survive and doesn't think he's "Too soft" (p. 56) anymore. The fact that Will finally recognizes that his fascination with Maren and the circus can be more than just that.

Overall, I'm glad that this is a school-read title for our book battle next year. I'm really interested to hear what the kids think.

References;

Oppel, K. (2014). The Boundless. Toronto, Ontario: HarperTrophy Canada.

I really dreaded having to read this book. I like the cover; I like almost any cover with a gloss detail, but despite the fact that it's one of our school reads/battle titles for next year, it's a WWII story and that's a total turn off for me. My colleagues love reading that stuff, and I just hate it. Fortunately, I was pleased to discover that politics and the war itself plays a very minor role in the story. In fact, it didn't need to be set in that time frame and location at all, really. In many way, it reminded me more of The Handmaid's Tale and 1984 than a war-story.

I was surprised by how long it took for the narrative to actually get to graffiti. With the title, I had expected it to take a much more central role to the story, but it's not really about that at all; it's a clever title with the homonym, but it captures less of the spirit than I expected. Ultimately, Tauber is undone by his carelessness and self-righteousness, not his vandalism.

At times, I was frustrated with the story. I didn't like how slowly it all seemed to be evolving, especially as it all seemed to lead up to the five kids going on the lam. I was much more interested in their lives on the run than I was in their lives in Leipzig. I did love Otto though, and I thought that the story and character development was well-crafted so that readers would feel as abandoned as Tauber when Otto effectively disowns him. That struck me far harder than when his father tried to do the same.

I was especially struck hard by two scenes. First, when Tauber almost assaults Ruth in her apartment. That was hard to read. The fact that I was reading it in the waiting room at the medical clinic did not help in the least. I started to cry which was made all the worse because I have an intense fear of crying in public and the scene was entirely unexpected. The second scene that got me was when Anniliese was shot (well, the entire scene there really). While it was satisfying to see her act instead of react, it was disheartening to see how she viewed the necessity of her sacrifice. I'm still torn whether she should have lived or not though. When she lived, I kept expecting to read something at the back about how her story was based on real-life events...because why else would she survive such an improbably situation?

I felt the writing was uneven too, though in the classroom that really just gives me more topics to discuss in class. It's sometimes just as valuable for students to see less developed writing (closer to what they might write) than masterful writing, and has enough holes in it that it has strong possibilities for students to write fanfiction:-)

1

1

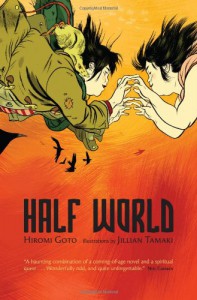

To start with, I love the cover of this book, but I remain confused: I believe the character on the left is Melanie in her mother's coat, with Jade Rat on her shoulder, and I'm guessing that the character on the right is her mother, though I say that only from the scarf and the facial similarities. What confuses me, or perhaps just annoys me, is that this scene never happens in the book. So while it's a compelling image, it doesn't actually relate to anything in the narrative, which to me is a failure in the design. I have a different problem with the illustration on page 183 which depicts the scene on pages 185-6. That's sloppy editing in the proofs. The image should interrupt the narrative instead of being placed in the convenient blank space at the end of the preceding chapter.

As far as the story goes, I generally liked the concept and parts of the story were compelling. I cried, for instance, when the Melanie wakes to discover her mother still missing and when the crows arrived at the penthouse. But I found the reliance on deus ex machina excessive; I have to agree with Aristotle that it's a device relied upon only in inferior dramas. The right thing showing up at the right time did not add to the fantasy of the novel for me, but only highlighted how the fantasy of the novel wasn't fully-wrought enough to allow the plot to move forward with such a device. I wasn't annoyed by the first fortune cookie, that seems appropriate that a fortune would be personalized to some extent, but the raccoon with the magic 8 ball was particularly stupid. Now, perhaps there's some allusion there that I'm especially missing that precludes having Melanie just trip over it being more useful, but really? I had no problem with the magic 8 ball in the story itself, but why the raccoon? To foreshadow the rodent transformation of the pendant? (That doesn't even work...raccoons aren't rodents.) And there's no logical relation between raccoons and crows for there to be a connection there. Being followed by crows in no joke though. The local family of crows doesn't like me (they try to nest next to my balcony), so I'm keenly aware of the gaze of crows and it can spook me easily. The description of crossing the chasm on their backs is an image I won't lose quickly.

In terms of plot, I also found the immobilization of Mr. Glueskin derivative of Oz. Materially it makes sense that ice would work, but it seems far-fetched to me that no one would have figured that out by now. Was he really so careful in the past to have waiters drop the ice buckets before eating them? He seems too impulsive for that to be likely.

I did enjoy the characters though. They weren't fully wrought either, but Melanie's doubts and fears are well presented, especially for a YA audience. The opening scene in particular is resonant for that age group, though perhaps finding solace in a bookstore is less so. Her revelation that she need control only her choices in chp. 13/14 struck me as a didactic bit of narration, however. Though an important realisation, I think I was most annoyed by the fact that she doesn't reach many conclusions herself. She doesn't seem to reach any form of independence or self-actualization in the story at all. Even in the fog at the end (one of my favourite scenes), she's following the voices of others who are telling her where to go. I think the fog is really the perfect metaphor for much of adolescence: feeling pulled in directions you aren't sure are correct, trying to resist, not always succeeding and having to find "That small, hidden place where she was so completely Melanie there was room for nothing else." (p. 202) That's a fantastic line, but I guess my main quibble with the story is that while the narrator tells me that place exists in Melanie, I don't feel as if I'm ever really shown what that place means. I don't feel I really know Melanie. So for her to have found herself is great, it's not a satisfying characterisation for me. I feel left out of what's apparently the most significant personal discovery she experiences.

1

1

My biggest reaction to the book was one of helplessness. I found that reading about Olemaun's disbelief at the experiences of her parents and sister as they tried to dissuade her from wanting to go to residential school, and knowing the reality that she would find when she got there from my own previous knowledge about residential schools was like watching a horror film. You know the scene where the girl is running from the murderer in the forest at night and decides to seek refuge in the abandoned cabin? How you want to scream at the screen that it's not safe? to keep running? But knowing that it won't matter and she'll die anyway? That.

Some people won't like the scrapbook feel to the book with its photographs, annotations, and appendix. Personally, I went through and pretty much read all the marginalia, photos, and extra material at the back first before I started the narrative. I've pretty much always done that when I read texts like this one with a variety of approaches to communicating information. And I find if I've read the vocabularly, for instance, before I encounter it in the narrative that it 1) allows me to predict with more confidence as I read and 2) allows my reading to flow with less interruption/confusion about unknown words.

1

1

A Little Verity for Kids

Kit Pearson's The Whole Truth is the story of two sisters, Maud and Polly, who are newly orphaned after the supposed drowning of their father and travel west by train from their home in Winnipeg, Manitoba to their new home on (fictional) Kingfisher Island, British Columbia to live with their estranged, maternal grandmother.

The third person, limited omniscient narrator tells the story from younger Polly's perspective. Consequently, the story begins with a ten-year old's response to grief: silence. She refuses to speak and instead observes the interactions between her fifteen year-old sister and their chaperone Mrs. Tuttle. Upon arriving in Vancouver, the girls are met by their grandmother and small extended family: Great-Aunt Jean and Great-Uncle Rand, the island's rector, and their university-aged son, Gregor. Together they travel by car ferry to tiny Kingfisher Island, located between Vancouver and Victoria where the girls will start their new life with the woman they now call Noni. But they need to adjust to more than just their location and family. No high school on the island means that the girls will be separated when Maud goes to boarding school in Victoria, and must to Polly's dismay, Maud can't wait to get there.

Once the girls are separated, their stories progress quickly. Polly has to adjust to life alone with Noni and her new role as the new student at the island school. Maud also needs to adjust to her new school, but the narrative perspective restricts us to Polly's experience of things. She knows only what Maud tells her in her letters home, which creates even more distance between the sisters. But her distance from Maud also allows her to become independent and eventually foster new friendships with Biddy and Vivien. Even so, Polly longs to tell someone how she really feels about her lonely situation, but has sworn to Maud that she'll never talk about their father. So she resorts to writing secret letters to him instead. She hides these in her hope chest, each one full of the earnest hope of a young child to return to her life before.

(show spoiler)

Despite all the unrest, Polly succeeds in growing up, being top of her class, and qualifying to move on to her sister's boarding school.

Personally, I was drawn to the book by the cover. I was at once attracted and annoyed. The cameo is attractive, but the fact the text isn't level irked me. Now that I've read the book, it makes sense. The book is written from Polly's perspective so ultimately the truth of the story is filtered through her mind (hence the text in the silhouetted head), but it's not the linear, easily solved mystery she wants it to be. Something is slightly off kilter and she senses it throughout her dealings with Maud, Mrs. Tuttle, and Noni; they're all keeping secrets from her and "treating her like a baby" (p. 32).

The book was longer than I expected (323 pages), but divided into three main sections that would make it easily teachable in a classroom as the transitions in Polly's life are clearly delineated. I was annoyed though at the quality of the publication; though its dimensions (5" x 7") suggests a trade paperback, it is in fact what the publisher HarperTrophyCanada calls a "digest paperback"--simply a glue-bound paperback which likely won't last long in a circulation library or a classroom. This will make it cheap for schools to acquire but expensive to maintain as a resource.

Pearson does employ some narrative techniques that make the book both worthy of study in an English classroom, but also problematic for some readers. The narration frequently includes Polly's thoughts, which while set apart in italics, may be confusing for some less-skilled readers. In addition, as the story progresses, she also begins to write letters to her father. These too are in italics and are helpfully dated to assist readers in understanding the progression of the narrative, but they also provide the opportunity for large jumps in the narrative timeline, at one point, for instance, jumping from July to September 1933 in the space of one page (pp. 192). While certainly useful from a narrative construction point of view given the long timeline the story presents of Polly's life, understanding what happened during the gap does require stronger inference skills on the part of the reader. This type of multi-modal narrative can prove especially difficult for less-skilled readers; even my grade 10 students have significant difficulty with a book like Shade's Children where the chapters are sequential but the inter-chapter elements present different viewpoints and timelines.

On the other hand, the inclusion of the letters does permit our limited narrator to present the thoughts of the other characters in ways other than dialogue and I enjoyed getting out of Polly's head, in part because I found her whining for Daddy so annoying. While Maud's letters from school are few, they do demonstrate how she is coping in her environment. The contrast between what Maud chooses to share with Polly and what Polly wants Maud to share with her helps to represent the growing gap between them. I could relate to that shift in sibling relationship as I went though similar changes with my brother (doesn't everyone?), but we at least still lived together full time and could hash out our differences in person without the limitation that asynchronous writing can place on real communication (though we admittedly would at times IM each other from adjacent rooms to avoid actually talking).

I did enjoy Polly's interactions with the other children on the island, however. In those Polly seems much more authentic than when stuck in her own thoughts. Making valentines and playing with her dogs were scenes that struck me as true. Not, of course, that real girls don't have thoughts and worries about her family like she does, but that's perhaps the problem: her worries are too real, too frequent, and not affected by the craft of the narrative as much as I'm used to. But perhaps that's my own bias against this type of children's literature, literature written FOR children. I'm a big fan of classic children's lit, but very little of it was ever written for children, and when it was the concept of childhood was much closer to that of the adult mind, so elements were rarely simplified or adjusted for young minds. And while I'm a huge fan of mysteries, I found I didn't really care what "the whole truth" was going to be, unless it would stop Polly's whining. I'm not familiar with any of Pearson's other work, so I don't really know if this type of voice is typical for her work either. I suppose if it's a hallmark of her characterisation then her fans would really appreciate this, but it didn't work for me.

My favourite part of the book had nothing to do with the girls though. It was the description of place. It's clear to me as a native British Columbian who has travelled the waters between the mainland and Vancouver island that Pearson has done some research, which given she also spent part of her childhood in the Vancouver area would be natural. And her ability to write imagery is effective. The island itself fascinated me, so I was pleased that Polly was so free to explore it and effectively report back. I love the initial description of the island:

The grown-ups pointed out a lighthouse that looked like a white candle. Mist rose from the steep sides of the island, revealing a blanket of dark firs. A few houses were perched her and there, some along the shore and some higher up. The ferry slowed down as it came towards another long, wide wharf. The sun flashed from behind the clouds and the waves turned from grey to silver. (p. 25)

And the appearance of the pod of orcas "all in alignment, like a whale ballet" (p. 303) near the end of the book seems to signal the aligning of all the parts of Polly's story as she begins to finally launch in into womanhood (except she's not really, as she's too young, but it reads that way...perhaps a cultural difference between teens today and those of the early-mid 20th century?).

Ultimately, I suppose I would agree with the conclusions in Amy Dawley's review of the novel that it would be a great choice for young readers who enjoy historic fiction (par.6), but would temper her conclusions that "the storyline, setting, character and plot development are all excellent" (par. 5) with 'for this age group'. Stronger, more mature readers will see weaknesses, some caused by the limitations of this point of view, others by the scope of the story. Dawley's discomfort with the subplots of Polly's vegetarianism and Maud's born-again-Christianity is well-founded, but, as Dawley asserts, these are attempts at more diverse character development which just don't seem to work as techniques. They seem to be attempting to highlight Polly's struggles with willpower and Maud's growing independence of thought apart from her family, but I think they'd be more effective highlighting the ultimate theme that 'people are complicated' (p. 322) and that they can be and do things which seem to counter their essential goodness and yet still be good...if only they were more artfully integrated into the narrative.

References

Dawley, A. (2011). The Whole Truth. CM Magazine. Retrieved from http://umanitoba.ca/outreach/cm/vol18/no6/thewholetruth.html.

Pearson, K. (2011). The Whole Truth. Toronto, Ontario: HarperTrophyCanada.

A book trailer for Sabriel by Garth Nix. This is one of my favourite books. Always happy to promote a great read, especially when it's first in a series and can hook kids into reading. Long live the Potter effect :-)

Immigrant Voices Part 2--An Argentinian-Jewish Coming of Age Novel

Littman, Sarah Darer. (2010). Life, After. New York: Scholastic Press.

282 pages. ISBN: 978-0-545-15144-3 (HC)/ 978-0-545-15145-0(PB)

On July 18, 1994, Daniela Bensimon turned seven and her world was turned upside-down. The terrorist bombing of the Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires devastated her family and country. This novel, from Sarah Darer Littman, author of Confessions of a Closet Catholic (Dutton Juvenile, 2005), follows Dani’s Life, After the tragedy. A few years after the bombing, the economic crisis takes her father’s business, he spirals into depression and Dani, her mother, and younger sister Sarita are forced to struggle through, without accepting the charity her father so despises. To make things worse, her friends are all emigrating to escape the Crisis. She feels alone and helpless and wants her Papá from Before back.

Her family decides to immigrate to New York City and start a new life. But Dani is lonely here too. By night living in a tiny “hovel” of an apartment where she tiptoes around her father’s depression and rage,and by day in a massive school where she doesn’t know the language and feels lost and bullied, she longs for a place of peace. At least she can communicate with her boyfriend on the Library computers But she comes to realise that her new world is full of unexpected joys: new friends at school, a new love interest, and a ‘mean girl’ who turns out to be just as affected by terrorism as Dani.

Dani’s first person voice rings true, though she and other characters show a wisdom beyond their years, but entirely consistent with their life experience. Littman seamlessly weaves the events of Dani’s childhood in Argentina and her Jewishness into the narrative. She also peppers the text with Spanish in a realistic portrayal of learning a second language. The books also includes emails, IM chats, and letters which give voice to other characters and add layers to the plot and character development. There are enough universal themes here to keep most students engaged, though those with experience immigrating, learning another language, moving to a new school, living with depression, or coping with tragedy will make more connections. It is a solid YA novel, not just a niche story about the Argentinian Jewish experience and families of 9/11 victims.

Recommended for grades 8-12.

Immigrant Voices Part 1--Video Games Can Be a Career Path

Yang, Gene Luen. (2011). Level Up. New York: First Second.

160 pages. ISBN: 978-1-59643-235-2

Grades 6-12

Review below.

Booktalks available here:

http://sites.google.com/a/ualberta.ca/immigrant-voices/book-talks/levelupbygeneluenyang

Gene Luen Yang, author of multi-award-winning American Born Chinese (First Second, 2006), returns with his Eisner-nominated graphic novel Level Up, a loosely autobiographical tale about Dennis Ouyang, the only child of Chinese immigrant parents, and his struggle to find fulfilment without disappointing his parents. Dennis aspires to play video games, and the book’s structure reflects that of a classic adventure game, each “level” increasing in conflict until he faces the ‘boss’of self-actualisation.

The introduction sets up the initial conflict: his father wants him to be a doctor. What follows through the levels of play is Dennis’ own hero quest.

First, Dennis flunks out of college because of his gaming obsession, and his mentors to appear in the guise of four angels. They remind him of a card his late father gave him years ago, the only time he said he was proud of Dennis. The angels coach him to pass his first test: earning his spot in medical school.

Once there, Dennis toils, with the help of new friends and the angels, to excel in gastroenterology, but he’s disillusioned. When one friend questions his commitment, he realises he’s living his father’s dreams, not his own.

After Dennis tells the angels he’s quitting med school, they retaliate and give chase, morphing into ghosts in pursuit. Dennis realises f they can become ghosts, he can be Pac-Man and consume them, but as he does so, he has visions of their symbolism: the regrets of his father. The reason for all their pressure to succeed now clear, he stops living vicariously for his late father. But despite winning trophies and prizes, being a pro gamer doesn’t make him happy. A chance meeting with a former patient whose life he had unknowingly saved makes Dennis reconsider his path.

Finally, Dennis returns to gastroenterology, where he discovers that gaming skills have a medical application too.

The first person narrative is illustrated by Thien Pham in a simple, monochromatic style. He deftly uses colour palettes to differentiate flashbacks, memories, and visions from the current action which helps reduce the reader’s reliance of descriptive text to navigate the time and reality shifts.

While coping with the pressures of being their parents’ legacy is something many students can relate to, it may resonate especially for children of immigrants. The fantastical elements allow Dennis to voice his internal conflicts, making him an engaging, though flawed, hero.

Highly recommended for grades 6-12.

Rebirth on the Pacific Coast Trail

Wild by Cheryl Strayed is a great memoir of her solo trek of the Pacific Coast Trail from California to the Washington border. She goes to escape many things in her life but comes to realise that she was also escaping to her authentic self. Her naivete about how to actually prepare for the hike mirrors her own lack of self-awareness...she thinks she knows what she's doing but discovers all too quickly she's clueless--typical of the learning conundrum, you can't know what you don't know until you know it--but that ignorance is exactly what allowed her to venture forth to start with, and also to NEED to tackle the PCT.

While all her travails on the trail were interesting and her voice is both raw and refined but entirely engaging, what struck me most was her relationship with water. It's obvious importance for hydration aside, her arrivals in trail stops with bathing facilities were moments of enlightenment.. The purification theme, washing off her past and emerging almost reborn to tackle the next leg of the hike and its challenges is something I think many swimmers can relate to. The meditative quality of moving through (or soaking in) water is much like the flow that she reached in the hike, but without all the blisters.

"In the bathroom, I shut the door behind me, turned on the tub's faucent, and got in. The hot water was like magin, the thunder of it filling the room until I shut it off and there was a silence that seemed more silne than it had before. I lay back against the perfectly angled porcelain and stared at the wall until I heard a knock on the door.

"'Yes?' I said, but there was no reply, only the sound of footsteps retreating down the hallway. 'Someone's in here,' I called, thought that was obvious. Someone was in here. It was me. I was here. I felt in a way I hadn't in ages: the me inside of me, occupying my spot in the fathomless Milky Way.

[...]

"I lay back and closed my eyes and let my head sink into the water until it covered my face. I got the feeling I used to get as a child when I'd done this very thing: as if the known world of the bathroom had disappeared and become, through the simple act of sumbersion, a froeign and mysterious place. Its ordinary sounds and sensations not normally heard or registered emerged.

"I had only just begun. I was three weeks into my hike, but everything in me felt altered. I lay in the water as long as I could without breathing, alone in a strange new land, while the actual world all around me hummed on." (Strayed, p.134-5)

Those who have travelled through Northern California and Oregon will recognise some of the landscapes and stops along her journey, but what's most interesting is recognising Strayed's growth through an essentially human experience.

Despite some swearing and frank (though not graphic) descriptions of sex, I would recommend this book for grades 10 and up as the themes would relate particularly well to students emerging (and planning for) adulthood (whatever they may think that means) and would provide many openings for rich discussion.

1

1